The Tennis Next Gen- A Case For Their Helplessness

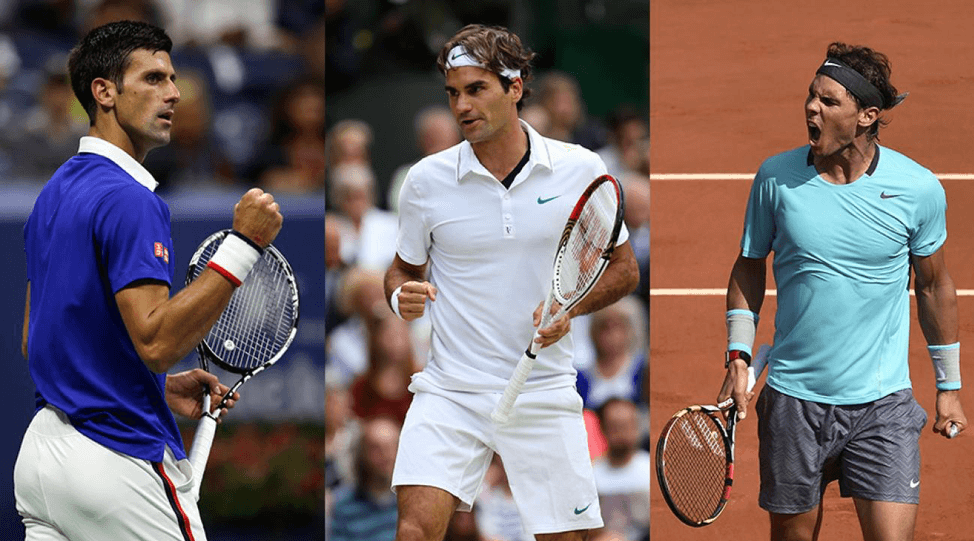

The domination of tennis’ big 3 has been relentless (Deporadictos)

As bells rang in the Swiss fields, the winds ruffled up in Mallorca. The children cried in their castles as yet another stage was set for what they saw as a battle between celestials. Clash number XLI. Forty-one- strangely the first five-setter Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal would ever play on American soil. It could’ve been their last, just like each of their matches in the last 3 years. But then, it never happened. Federer fell to ‘baby Federer’, Grigor Dimitrov in the final 8.

This was the first time since 2010 that neither Federer nor Djokovic, who limped out of his round of 16 match had made it to the semi-finals. The big 3 era is fading slowly. Too slowly. One would have to go all the way back to 2004, for the last time neither of these two or Nadal made it to the last 4. Or 2005, since neither of the three have been in a major final, barring a couple times from a possible 60. To put this in context, the intense Sampras-Agassi rivalry couldn’t last a record like this for more than a year. These are actual statistics; mind-boggling numbers that tennis fans have been spoilt with.

These are juggernauts, forces that one sits back and appreciates, cheers and applauds as fans in their respective countries. But to tennis playing generations over the last 15 years, they are untouchable demons.

Imagine yourself as a promising star in your prime 20s, the best your country has ever produced, having won all the local tournaments that are to be won. You enter a major tournament with your dreams and hopes still intact, i.e., before you face either of them, the greatest, the toughest and mentally strongest players to have ever wielded a racket on tour. Before their talent prevails, yours will break as you bump into either one of them every tournament year after year. A brick wall sealed with a magical chant. Soon enough your soul gets crushed and you fall prey to greatness as per standard procedure.

In contrast, you may lighten up, start appreciating the miracle in front of you and accept where you lie. That’s when the weight of your pressure to perform truly lifts, you play the game of your life, and sneak out a win. It doesn’t happen often, but once every few years some of you definitely do manage one. That’s when you realize you face another one of them in the next round, and you leave the tour for good. That’s what the next generational has felt like every month for the last 15 years

Where is the next generation?

It’s been a staple question amongst tennis fans over the last decade. Dimitrov, who downed Federer in this year’s US Open, was termed as baby Federer owing to his one-handed backhand (and nothing else that seemed similar). He was touted to be the next big superstar as Federer ‘waned’ entering his 30s. Dimitrov, 28 now, hasn’t reached a single major final, as Federer continues to rack his tally while nearing his 40s.

At 29 years old, Kei Nishikori, the shrewd Japanese has reached and lost one major final. Dominic Thiem, the assertive Austrian, the next gen clay court specialist, has managed to reach and lose two Parisian finals to who shall not be named at Roland Garros, is 26. An age at which ‘Rafa’ Nadal had already won 11 majors and reached another 5 major finals. And although Thiem might just be the first to win a major amongst the next gen, his record in non-clay majors is best to say, atrocious, only reaching the quarter-finals once.

Thiem is one of the brightest stars of the next gen

As far as clay specialists go, Rafa, often termed as ‘only a clay specialist’ by the game’s wicked fans has won as many non-clay majors as John McEnroe and Mats Wilander have in their entire careers.

The rest of the next gen is too young as well as inexperienced. But only lucky enough to perhaps have more years at the top without the big three. All said and done, Bianca Andreescu’s win last week in the women’s final puts a female major winner who was born in the 2000s before a single male major winner born in the 90s. That’s the gap that the big three created. A decade of talent without a winner’s trophy. A void. Impenetrable. Infallible.

This is why this isn’t a dismissal of the next gen’s achievements, least of all a comparison of whatever they have won to what the big three have. What this is, is a case for their helplessness. And it’ll better be explained through last week’s battle between Rafa and Daniil Medvedev in the final at the Flushing Meadows.

The battle of generations

The final was a final of two halves which involved a twist of an ending which really wasn’t a twist in the first place. The first half belonged to Rafa. It belonged to the routine watchers, the bookies and writers who had already readied an article because they knew what was going to happen.

It was not a massacre, the likes of which we see when Rafa shifts to third gear. It was a steady dominance. Every time Medvedev got on top, his Spanish opponent shifted tactics, slicing it low, spinning it high, until he was on top again: on the scoreboard and on the young Russian’s mind.

Class. Quality. Experience. When it seemed like Medvedev almost had it, a combination of all three showed. Rafa hitting monster forehands as you stand there as a 23-year-old, playing your first final, your throat as dry as ever. Not to say the occasional fist bumps and rallying cries that send most players packing their bags before matches even warm up.

And then just when you prepare yourself enough to deal with all of it, the very next point you see a combination of so many mixed shots in a single rally, that you wonder whether any coach or book can even teach you. And just like that you’re down a set. Then two. With the crowd on your back and the game’s toughest fighter pumping and running across the net, just what do you do, as a 23-year old, playing your first ever final?

Robbie Koenig said at the beginning of the third set that Medvedev will have to do what no one has ever done against Rafa in a major final, winning from 2 sets down. And then he went down a break as well. However, everyone casually waited for the inevitable: Rafael Nadal’s 19th grand slam title.

The clock hit 2 hours and 15 mins. Rafa was two sets and a break up. A routine 20 minutes of play left before he could win back the coveted prize from Djokovic. From that point on, the match went on for almost another 2 and a half hours. Yes, 2 and a half hours.

Did Rafa slip up, when he missed the overhead in the third set, at 4-4 trying to convert a break point that would set him up for the title? Or should the romantic in us give the credit to the young Russian who played severely clutch tennis, as he fired a forehand fast enough to be devoid of any loop and accurate enough to paint most canvases, to set up and convert set points of his own later in the same set. More of this swashbuckling tennis, and Medvedev leveled the game with 2 sets each, looking to do the impossible. Not beating Rafa when down 2 sets, but moreover, looking to beat either of the game’s masters at the game’s biggest stage.

And despite all the momentum against him, Rafa found a way as he saved multiple break points in his very first service game playing even more clutch tennis. He eventually won a ferocious forty shot rally to convert his break point. In that moment he was more experienced, he was more class, he was simply more Rafa.

And yet the match had more twists. Rafa got his time violation down a break point in the service game that was supposed to win him the championship and he blew the resultant second serve. Then, he wasted multiple championship points before facing another break point that would make Medvedev draw level in the final set.

How does a player maintain his cool in a situation like this? A player doesn’t. Not a mortal player. And there is nothing Medvedev could have done.

Despite Medvedev’s best efforts, Rafa’s class and experience shone through (Teller Report)

Easy to say it in hindsight, but then it’s not like no one said Rafa wouldn’t win. While credit must be given to Medvedev for making it look like he could do what he never would.

The narrative

Medvedev came close. But it wasn’t enough. Nothing is. So how does it change the narrative?

How are the big three to be beaten? They are fit and they are generational talents. But even if a younger, fitter, and equally talented wonderkid comes across, how is he to compete against the sheer experience. We’re talking about players who have played the greatest matches in the history of the sport, who have been in every kind of situation. Messiahs who don’t have nerves of steel, but rather no nerves at all.

How is he to compete against the magic that the crowd provides to them. It’s something that Medvedev managed with his play despite having an altercation with the crowd earlier in the tournament, something that he turned around in a touch of extreme spirit and class. So, is it the best that he could have done? Is it the best anyone could have done? Most certainly, a bittersweet yes.

How does it change the narrative? The bookies still had it their way, the casual fans read that Rafa won his 19th major in the morning paper. But it changed the articles of all the writers who had written a little something before the tournament had finished. Yes, Rafa won, yes, another next gen star lost and yes, we’ll all hope that Medvedev goes on to prove his worth in the coming years. But what he showed, that no one else could, is that the gap between the big three and the world is closing. The biggest thing that he could show was that the big three are actually becoming mortal; that they’re probably capable of losing a slam.

But will they actually lose one? Probably not. So, what do the next gen stars do? Do they pray to the Gods? They do that, and it doesn’t help. Because Gods cannot change what these three do. They can’t change the inevitable; that Nadal would win his 4th US Open. Everyone knew it the moment Djokovic and Federer crashed out. That he would pull himself one closer to Federer. That what we are witnessing, we will not see in our lifetimes. And we won’t know it until a few years later.

This is nothing less than Johnson and Bird, Ali and Frazier, Senna and Prost, but with three of them, all complementing and enhancing each other. Poetry, that will probably end with an equilibrium of 25 majors for each of them. Before they prove tennis, fans wrong again. Before all three of them play for another 10 years, winning 10 more grand slams, as a few more generations of tennis pass by in defeat, in helplessness, in awe.

Read More

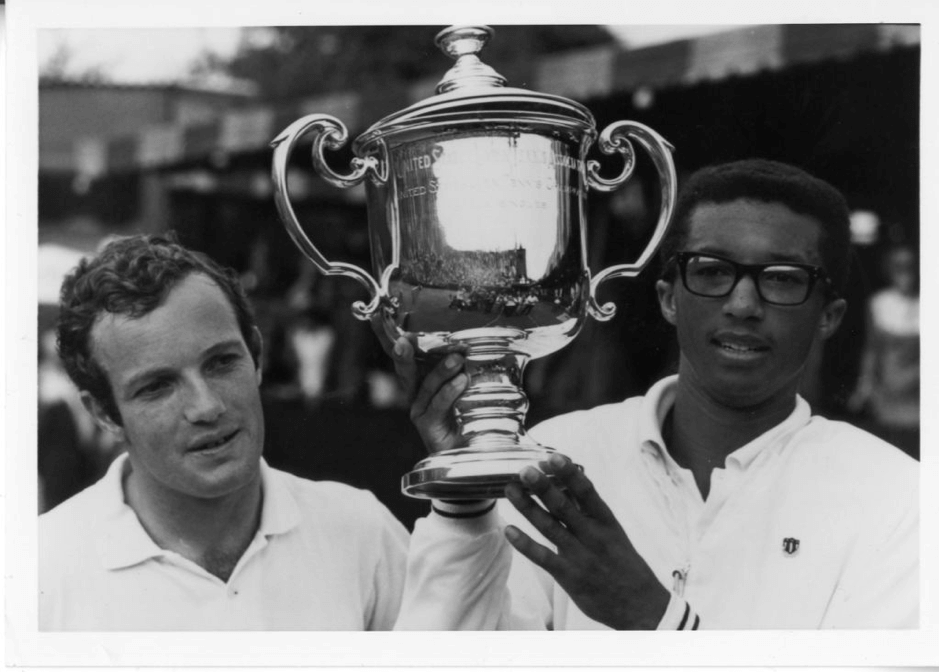

THE 1968 US OPEN: A NEW CHAMPION, A NEW ERA

AVICHAL GUPTA \

THROWBACKS

BIANCA ANDREESCU: AGAINST ALL ODDS

OUT WITH THE OLD, IN WITH THE NEW: A CHANGING OF THE GUARD AT FERRARI?

KABIR ALI \

FEATURES