METAL, COMPOSITE AND GRAPHITE: THE DECADE OF OPTIONS

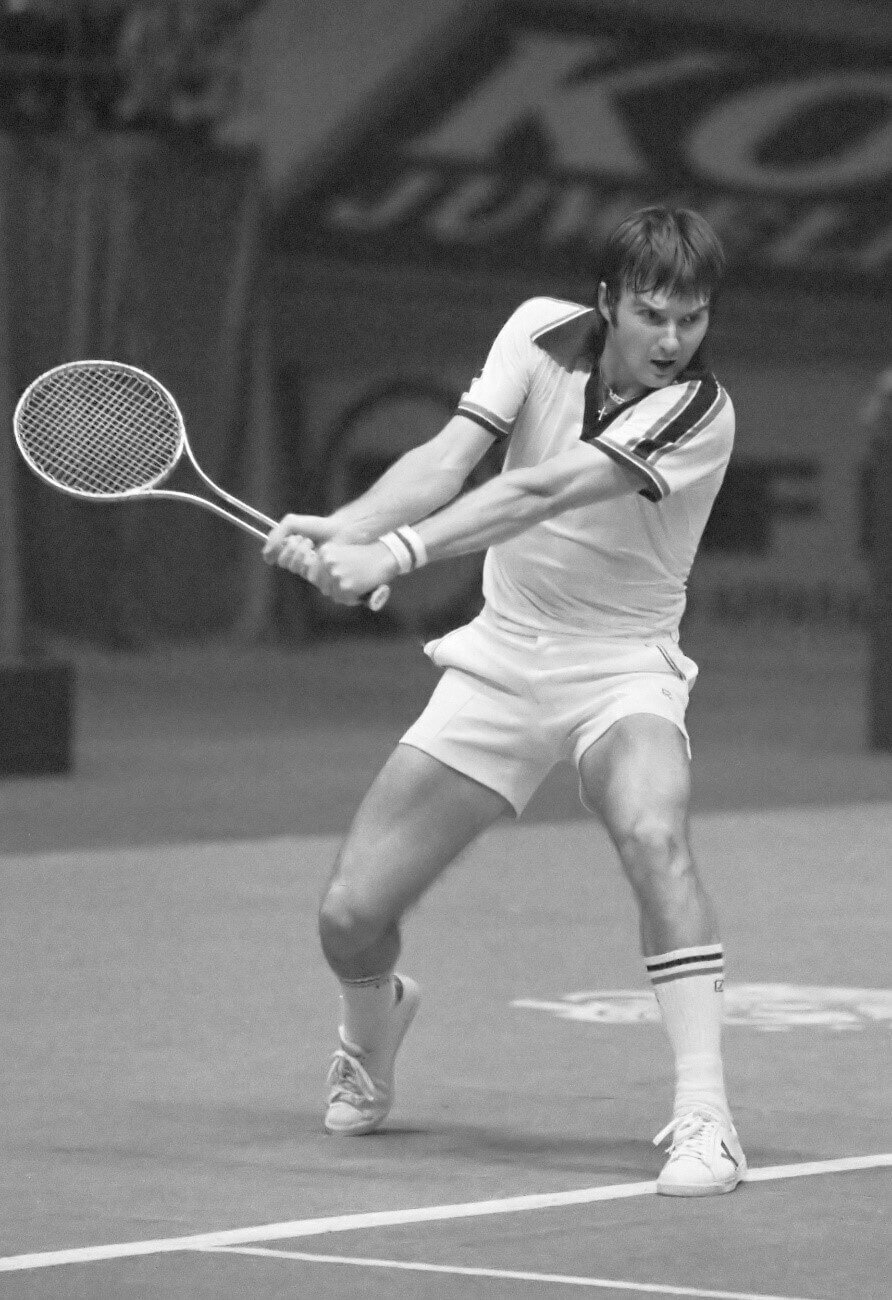

It’s often said that change is the only constant in life and if one were to map out the racket preferences amongst the top players of the 80s and early 90s, they would find that unlike any other period in the game, the number of options (with regards to the manufacturing and design) in terms of rackets was at its peak. There were players who preferred the new composite frames because of their weight and durability while some like Björn Borg used wooden rackets to win some of the most prestigious tournaments in the world and then there were the new graphite rackets. These carbon-based made pieces were the rage amongst the new generation with the likes of Becker, Sampras and Agassi showing effectively as to how they could be utilized by serve and volleyers as well as the baseliners on tour.

Another change that took place during this period was the growing head-size of rackets. Many players often shocked their opponents with their large sweet spot weapons unleashing ferocious shots. In 1981, the International Tennis Federation (ITF) first established the official rules for racquet sizes. The rule today states that a racket “shall not exceed 73.7 cm (29.0 inches) in overall length and 31.7cm (12.5 inches) in overall width. The hitting surface shall not exceed 39.4 cm (15.5 inches) in overall length and 29.2 cm (11.5 inches) in overall width.” This ruling was very effective in curtailing several enthusiastic racket manufacturers and curbed the ever-growing size of tennis rackets. Thus, bringing in a limit within which the tools of the trade could be moulded.

Since the 1980s, high-end tennis rackets have been made from fibre-reinforced composite materials, such as fibre-glass and carbon-fibre. The advantage of these composite materials over wood and metal was their high stiffness and low density, combined with manufacturing versatility. Composites provided the racquet engineer with more freedom over parameters such as the shape, mass distribution and stiffness of the racquet, as they can control the placement of different materials around the frame.

While wooden rackets had small, solid cross sections, composite rackets had large, hollow cross-sections to give high stiffness and low mass. The increased design freedom offered by composites was demonstrated with the introduction of ‘widebody’ rackets, such as the Profile by Wilson, in the late 1980s. Widebody rackets had larger cross sections around the centre of the frame than the handle and tip, to give higher stiffness in the region of maximum bending.

A frame that suits your game

The game of tennis is quite unique in the sense that one person’s method of playing the game could look entirely alien to the other and yet be as effective as any other. One of the very few players to continue into the 1980s with a wooden racket was the legendary Björn Borg who with his Donnay racket continued to dominate men’s tennis till his sudden retirement in 1983. He did so because he had visibly mastered the game on his favourite racket and was able to negate the advantages gained by his competitors on other newer frames. He was clearly an exception to the rule as most of his peers had by this time switched to the lighter and more consistent composite frames.

There’s then the case of Ivan Lendl who switched to a graphite/fibreglass model in 1979 with the Kneissl White Star Pro and then to Adidas in 1981. The difference amongst those two rackets was quite minimal and he essentially played out the rest of his career with the same frame, which considering the amount of changes witnessed during the decade and the fact that he retired in 1994 is almost unbelievable. Lendl was known as one of the toughest competitors with and an ice-cold temperament, his was again a situation of a player understanding his game and his equipment. The man from Ostrava would eventually finish his career with 8 Grandslam titles (the last of which was the 1990 Australian Open) which speaks volumes of the level of player he was.

Surface Demands

The professional game moved increasingly towards the hard courts as they offered a variety of benefits over the grass and clay versions. The most lucrative of those benefits was the televised version of tennis under floodlights, various tournaments were set up on the American and Canadian Hard Courts while Indoor Courts started popping up in Europe. This meant that the demands of the game were also changing and so were the requirements of its players. The metal frames slowly started giving way to composite rackets who along with graphite/fiberglass became the preferred options.

The modern player now was a baseliner and because the hardcourts offered consistent bounce and an even trajectory of the ball this era saw the arrival of some unbelievable returners, the greatest amongst them being Andre Agassi. The American made return of serve a weapon and would often break the morale of his opponents before they had even stepped on to the court. Amidst all this powerplay and supreme athleticism there was a quiet and deadly player from Potomac, Maryland who entered the men’s game at the end of the 80s and completely owned the game in the 90s. Amongst the many double handers here was a guy with a single hand backhand and a remarkably strong net game, he would serve and volley at will and rarely be over powered from the back of the court. This of course was Pete Sampras and as Bjorn Borg did before him in the 80s, he ruled the world with a hint of a throwback style of tennis (while adapting seamlessly with the modern game). Well, as they say, every theory has its exceptions’, perhaps in tennis, the exceptions often are legends.

Read More

THE AGE OF METAL

AVICHAL GUPTA \

THE MAKER AND ITS GAME

THE ERA OF THE SHORT GAME- WOODEN GLORY

ANANYA CHANDRA \

THE MAKER AND ITS GAME

THE DAY SÖDERLING TOPPLED THE KING OF CLAY

ATUL KUMAR MAURYA \

THROWBACKS