THE ERA OF THE SHORT GAME- WOODEN GLORY

The year was 1993, a local all wooden racket tournament was underway, swarms of white clothing once again juxtaposed the greens of a tennis court. The audience would patter applauses in between occasional yawns and the players in short sleeved tees and even shorter shorts clashed against one another, most of them experiencing an unfamiliar struggle – that of playing with a wooden racket. An amateur playing his first all wooden racket tournament having narrowly lost his first set, would sit on his chair, sweating. He hadn’t expected it to be anything like this, the racket was heavy and the game was different. It was like being transported to the games he had seen on television, to an era long gone, to an age of wood.

Engravings on wood

If we rewind the clock by three quarters of a century, one would have the chance to see a lanky Bill Tilden wearing all whites feature in a silent instructional video, teaching kids the best way to hit a tennis ball. With forehand swings smashing the ball like a squash racket would, backhands contrastingly feeble and footwork that would seem alien in today’s game. Bill and the children would hold in their hands a wooden racket which was long throated with a small head (frame size), flexible in its build and heavy to lift or maneuver-all three characteristics that would make it far more difficult to play tennis. A smaller head size that would give the racket a sweet spot the size of a peanut; a racket that would be far less forgiving for ill-timed or poorly contacted shots, a lower degree of flexibility that would impart less power and spin on the ball and a much heavier frame which would require muscular arms to play with even for a few minutes, let alone an entire match. Why would anyone play with this racket?

Tennis players weren’t blessed with a plethora of options for well over a century, the wooden racket saw little development or advancement. Players practiced with wooden rackets from an early age and grew up with perfect technique. Perfect half volleys, perfect punches, perfect approach shots and really strong arms. Bill Tilden’s ‘cannonball’ service was generated from his uncanny ability to find the sweetest spot of the racket. There was no other way to play with a wooden racket. There was no margin for error. Wooden rackets would also warp, crack and dry out easily. But they were cheap to produce and cheaper to buy and that’s all there was. Generations of tennis players and aspirants growing up learning a game, which its most fundamental tool made it anything but easy to learn.

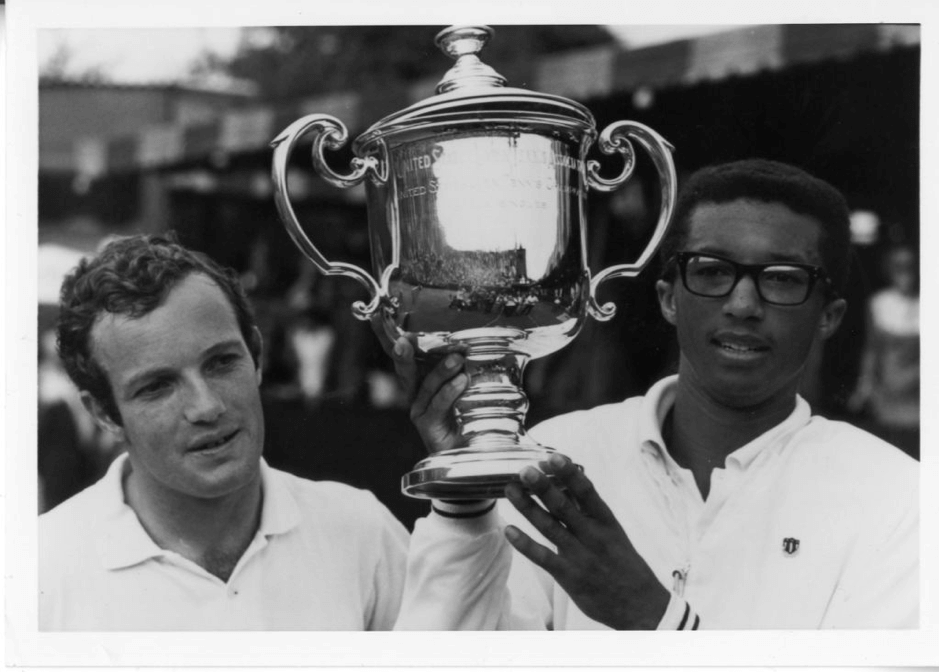

Years passed and many stalwarts of the game kept engraving their names on these hallowed wooden frames. Fred Perry, Don Budge and Pancho Gonzalez outclassed everyone throughout the 1930s and 40s. By the time players like the physically fit Roy Emerson, Lew Hoad, and the great Ken Rosewall came in in the 1950s, it would be almost a century without any advancements in racket technology or in the game of tennis. The grass courts were still common and so were awkward bounces. The grass would always wear off as the games would go on and the players would opt for a wonderful tactic to avoid bad bounces hence serving and volleying was a major part of the game and continued to be so. The rackets didn’t make it easier to volley but then playing from the baseline was far tougher.

The Dawn of Metal

Metals were still not durable and most players on the tour were still using wood. Pancho Gonzalez swore by his Spalding piece and Rosewall stuck with his Slazenger for all the decades he played the sport. New wooden rackets were being released and still being endorsed by famous yesteryear players for the coming tennis generations, like the famous Wilson Sporting Goods “Jack Kramer” autograph which became the best-selling tennis racket of all time. Lew Hoad never played with a metal racket; at least not professionally. His wife Jenny used to say that every now and then he would borrow one from Newcombe, Gonzalez and Rosewall, but would break them far too easily. He’d break the wooden frames as well, but at the time, they were cheaper to replace. Players like Hoad stuck to wood; not like he needed the extra power generated by metal rackets anyway.

Tennis as a game wasn’t looking for power either. The game with the wooden racket was more about tactics and outsmarting the opponent, because generating spin wasn’t easy with heavy and flexible rackets. Rosewall was a flat ground-stroke maker with a devilish backhand; few remaining witnesses still claim it to be the most ferocious backhand they have ever seen. When asked recently if he still recognized an almost unrecognizable game, Rosewall replied – “I struggle a little bit to do it, but tennis is still my sport. Of course, training, diets, recovery time, physiotherapy, tactics and racket technology are very different than when I was playing. You couldn’t hit topspin balls or use so much power.” Generating top spin wasn’t easy with wooden rackets. But tennis, like all sports, produced an exception.

A player that defied norms and changed the game forever – Rod Laver. With his continental grip and unorthodox movements, he generated top spin on his forehand drives and more surprisingly on his backhands as well the likes of which had never been seen before. In a recent interview, Laver commented on the difficulty of playing top spin all those years back.

“Yes, I used to hit with heavy top-spin but when you look at the little rackets I played with, the Maxply Dunlop, you had to hit the very centre all the time. I had my share of miss-hits. I was accused of hitting them off the wood, winners over their head, drop shots, whatever, and I’d say, ‘Well that’s the way it is, guys!’.”

Acknowledging that the game today was twice as good and at a level far better than what it was in his day, Rod Laver continued.

“You get one of those big-headed rackets, it’s so easy to play with them. Just beyond the end of my career, I started playing with one of these rackets and I thought ‘Jeez, I can get back on tour again!’ It was huge.” If you were smashing, you couldn’t put the ball away with a Dunlop, but these metal and composite rackets, you have so much more speed, easier to volley, get the depth on ground strokes without any effort. And that’s where I see today’s players having an advantage over those of us who used wooden rackets.”

As it happens in life eventually the new supersedes the old and it was inevitable that the wooden rackets would lose out to larger, lighter and more powerful metal rackets.

An end to the gentle touches

It was sometime in the 1980s, an amateur sat on his chair, sweating, the wooden racket was heavy and the game was different. Hitting the sweet spot with every shot wasn’t easy at all. He had been spoilt by his trusty graphite head which was far more forgiving. Playing with a wooden racket was as hard and as it was frustrating but it was also the closest to tennis he had ever felt. He had never enjoyed a tennis match more. For once, he wasn’t pounding the ball but caressing it, he wasn’t sniping his shots but placing them, he wasn’t finishing his rallies but outwitting his opponents. Sitting on his chair, he would toss a ball with his graphite racket, and think to himself – playing with this would feel like playing with a giant pillow.

After being much the same for over a century, the game of tennis had changed all of a sudden, the time of the wooden rackets had come to an end. Was it just a precursor to an era where marketing would take over and stars would drown in multi-million sponsorship deals with graphite rackets having sweet spots the size of Australia? Or was it an inadvertent end and a shift to a more powerful, more watchable game of the sport?

John McEnroe said, “Every match deserves to be thought of in the same way as a painter in front of a still white canvas. At least, that’s tennis that I’d like to see.” Whether McEnroe’s wish died or became truer with the passing of wooden rackets remains a matter of personal preference. But for many, the game was purer with a wooden racket. A game you could control more, and feel more.”

Regardless of one’s opinions by the time the technology evolved and new rackets became unsaid mandates in every tennis player’s setup, wooden rackets were already in cabinets. The Open era coincided with the advent of the shift. The advanced rackets were too good to not play with and in comparison, they felt like carrying a feather, generating cannonball services in every street across the world and not just from the talented and strong arms of Bill Tilden. And so, the wooden rackets bowed out, as brushes once wielded by the legendary artists of the game, paving the way for what the game is today. It led to an era of metal frames and an end to gentle touches and tactical strokes. It led to an end of the age of wood.

Read More

THE DAY SÖDERLING TOPPLED THE KING OF CLAY

ATUL KUMAR MAURYA \

THROWBACKS

WIMBLEDON 2009 MEN’S SINGLES FINAL: ONE FOR THE AGES

ATUL KUMAR MAURYA \

THROWBACKS

OUT WITH THE OLD, IN WITH THE NEW: A CHANGING OF THE GUARD AT FERRARI?

AVICHAL GUPTA \

THROWBACKS