MARACANAZO ’50: THE DARKEST DAY IN BRAZILIAN FOOTBALL

Due to the Second World War, the 1942 and 1946 editions of the World Cup were never even deliberated upon. Lives were lost, economies crumbled, people misplaced and trepidation survived in the hearts of people for a fair amount of time even after the war ended in 1945. With Europe left in ruins and plenty of Asian countries not wealthy enough to be hosting a World Cup, FIFA almost felt it would be impossible to conduct football’s most elusive competition. But then, Brazil came forward and opened its arms, much to the delectation of the sporting planet. Their only condition was to organize it in 1950, as opposed to the proposed idea of 1949. That’s how the foundation was laid to the most infamous FIFA World Cup ever, a tournament which was expected to resurrect the spirits of those who were physically present but mentally absent, considering football was far from being a priority with the world in one of its most hostile and warlike state.

The four years leading up to 1950, Brazilians counted down each day for the competition to quench their thirst for football first and more importantly, hope. The wait was unbearable.

A 15-team World Cup eventually kick-started with 13 teams spread across 4 groups. Group 3 and Group 4 had three and two teams respectively, whilst 1 and 2 had four teams each. The winner of each group (Group 1 – Brazil, Group 2 – Spain, Group 3 – Sweden and Group 4 – Uruguay) played a final round-robin in which the winner of which was to be crowned world champions. Interestingly, the 1950 edition was the only FIFA World Cup which didn’t have a final. As it turned out, Brazil and Uruguay, who were scheduled to play the final game under the round-robin format were also the teams touted to win the tournament.

The Seleção entered the game with 4 points to their name, winning two matches whilst Uruguay had 3 points. A draw would have done it for the hosts and for the first-ever World champions, there was just one door to break open.

That World Cup meant everything to the country and their side had nothing else in mind but to lift the trophy at the Maracanã, a stadium built specially for this tournament. 16th July 1950 was supposed to be the day when dreams turned to reality for every Brazilian watching on and during a period starved of hope, football seemingly answering all of life’s questions looked imminent. But instead of joyous tears, colourful cheers, victory parades and a kiss on the Jules Rimet Trophy, Brazil were deterred, scars of which still remain fresh in the hearts of their faithful.

Football can be cruel sometimes

Brazil had scored 13 goals in the opening two games of the final round and were entering the final with a strut as they looked destined to lift gold on home soil. Their South American compatriots in Uruguay on the other hand did not have as flamboyant a run as they squeezed a 2-2 draw against Spain and Óscar Míguez’s late winner saw them trump Sweden 3-2.

Juan López marshalled his Uruguayan side tactically as well as mentally. He had instructed his players to play deep and defend with their lives at stake, which was the only way they could’ve stopped Brazil from scoring. Apparently, Uruguayan captain Obdulio Varela opposed his manager’s defensive mentality, but an emotional pep-talk that followed from Lopez was said to have impacted the team immensely. After all, the stage was set for the 199,854 frenzied spectators inside the Maracanã (which remains the largest attendance for a football match, according to Guinness World Records) to see Canarinha taste the sport’s ultimate success. The Uruguayans had to go about their plan based on the will to execute and not buy into the emotion of the occasion.

As the game kicked off, the Uruguayan defence nullified the Brazilian attack in the first 45, which stunned the Maracanã and the well-drilled machine created by López managed to make sure the hosts were kept at bay. Things took just two minutes to flip on their head as legendary striker, Friaça’s searing run into the box left the defenders dismantled and he neatly guided it past the keeper’s right, into the net. Fireworks went off in the crowd to perhaps the loudest cheer the beautiful game has ever witnessed. Skipper Varela was furious and he demanded the English referee George Reader to call the goal as offside but the official had made up his mind and his decision.

The Samba in the crowd was soon to be muted and their joy was a bit too short-lived as Uruguay took the attack to the hosts and dominated the next few minutes. Feeding off Alcides Ghiggia’s brilliant trickery on the right-wing was Juan Alberto Schiaffino who tapped home the most unforeseen of equalizers one could think of. Uruguay were back in it and no one could believe what they were witnessing. Yet, to convince any of the 199,000-odd supporters in the crowd that a defeat was in sight was an impossible task and rightfully so as Brazil remained the outright favourites, despite conceding.

However, their most dreaded dream came true when Ghiggia, who scored the first goal, made another electric run down the right flank and squeezed his shot past Brazilian ‘keeper Moacir Barbosa’s near post. The Brazilian backline was exposed on the most important day of their lives, tears had already started flowing and as the Uruguayans held on, the script for one of the sport’s greatest upsets was written.

After 90 minutes, it was Brazil 1, Uruguay 2.

A national tragedy

You’ve got to beat the best to be the best

As gut-wrenching as the game was for the Brazilians, the aftermath’s intensity was on an unprecedented level. A fan had committed suicide and three people inside the stadium were rushed to the hospital having suffered a heart attack. As some people later on recalled, a distressed crowd left the stadium so frantically, they luckily survived a brutal stampede. Maracanazo is remembered as one of the greatest tragedies in their nation’s history, for the toll it took on the mental health of the locals.

Some journalists famously wrote that the nation forgot to smile for a good 12 months and the trauma of the defeat continued to haunt them until the next World Cup. 33-year-old Dondinho, a striker whose name was well familiar in the streets of Minas Gerais, followed the game on a radio at his residence in Três Corações. When he was left in tears after the game, much like the entire nation, his 9-year-old son promised that one day he will bring that World Cup to brazil. 12 years later, that kid brought 3 World Cups home, scoring 15 goals and assisting 10 times in 4 editions. The name resonates even without a mention.

Brazil didn’t get to host for another 64 years. When they finally did so in 2014, with an expectation to make amends for what happened in 1950, history repeated itself, but this time at the Belo Horizonte. 7-1 happened, leaving many torn as to which one was a bigger tragedy.

One game, an array of emotions and a million tales. While there have been many football matches before and after the 1950 World Cup final between Uruguay and Brazil, very few provided a result like this. It was as shocking and harrowing as it was immortal. On this day in 1950, Odbiolo Varela and Augusto da Costa led their respective units out to play the most infamous games in the sport’s rich history.

Read More

WHY BAYERN’S TRANSFER MODEL LEAVES THE REST OF EUROPE IN THE DUST

JAI SINGH \

THE DRAWING BOARD

DISSECTING WHY ENGLAND’S SIDELINING OF MICHAEL CARRICK REMAINS INEXCUSABLE TO THIS DAY

UTKARSH GOKHALE \

THE DRAWING BOARD

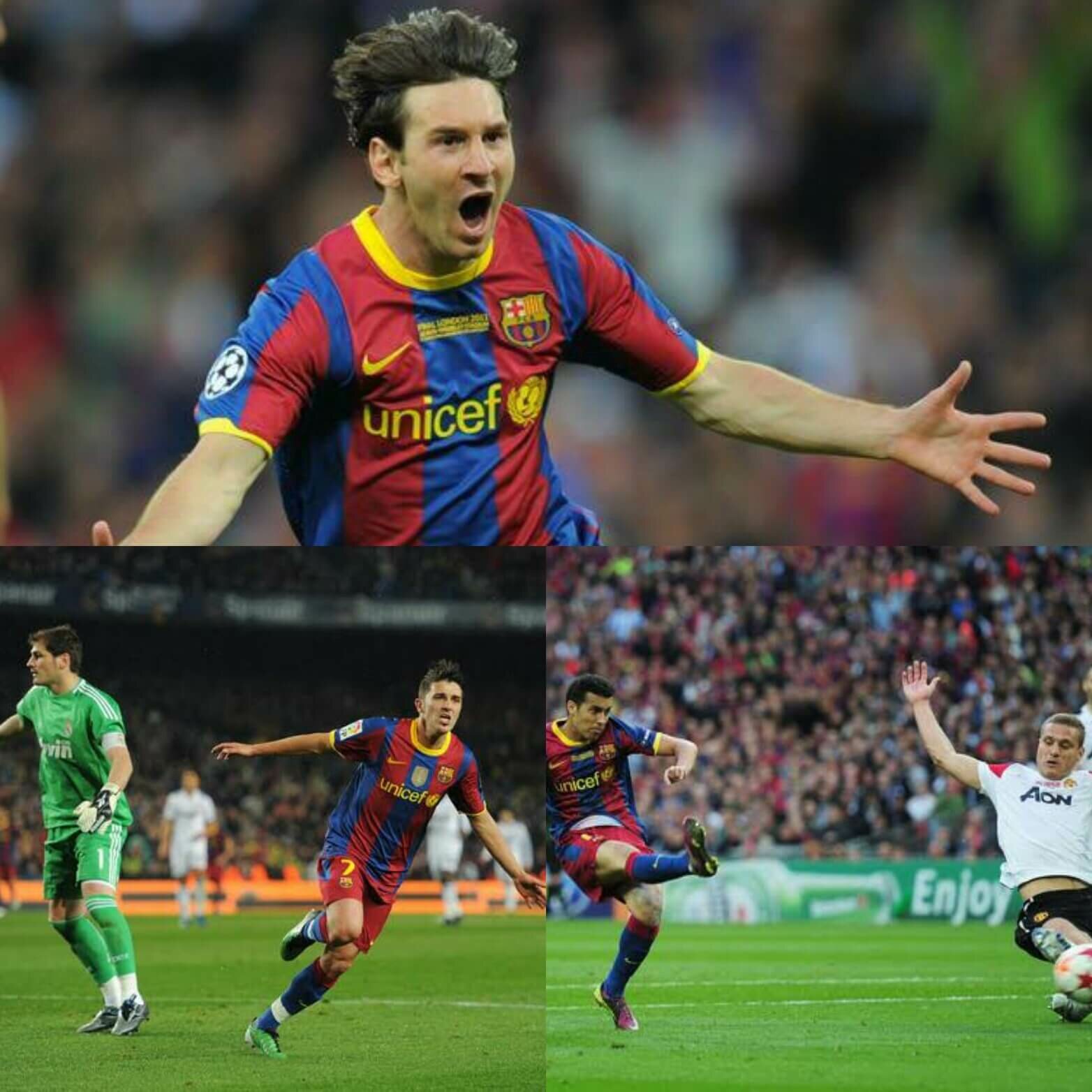

THE REAL MVP: WHEN MESSI, VILLA AND PEDRO JOINED FORCES AND TOOK SOULS

ADITYA GOKHALE \

THROWBACKS