THE AGE OF METAL

Just as tennis prepared to usher in the transformative Open Era, lesser known developments in racket technology began to surface in the late 1960s. Tennis legend Billie Jean King and her compatriot Clark Graebner took the 1967 U.S. Championships at Forest Hills by storm, wielding the revolutionary Wilson T-2000. The game’s first stainless steel frame, the T-2000 was a licensed version of the racket designed by legendary French tennis player and fashion designer René Lacoste in 1953. King went on to win her maiden U.S. Championship title without even dropping a set, while Clark Graebner reached his first Major final only losing to legend John Newcombe.

“We made an absolute sensation of that racket”, quipped Billie Jean King, looking back at how the Wilson T-2000 became the first commercially successful tennis racket that wasn’t made of wood.

The Standard Bearers

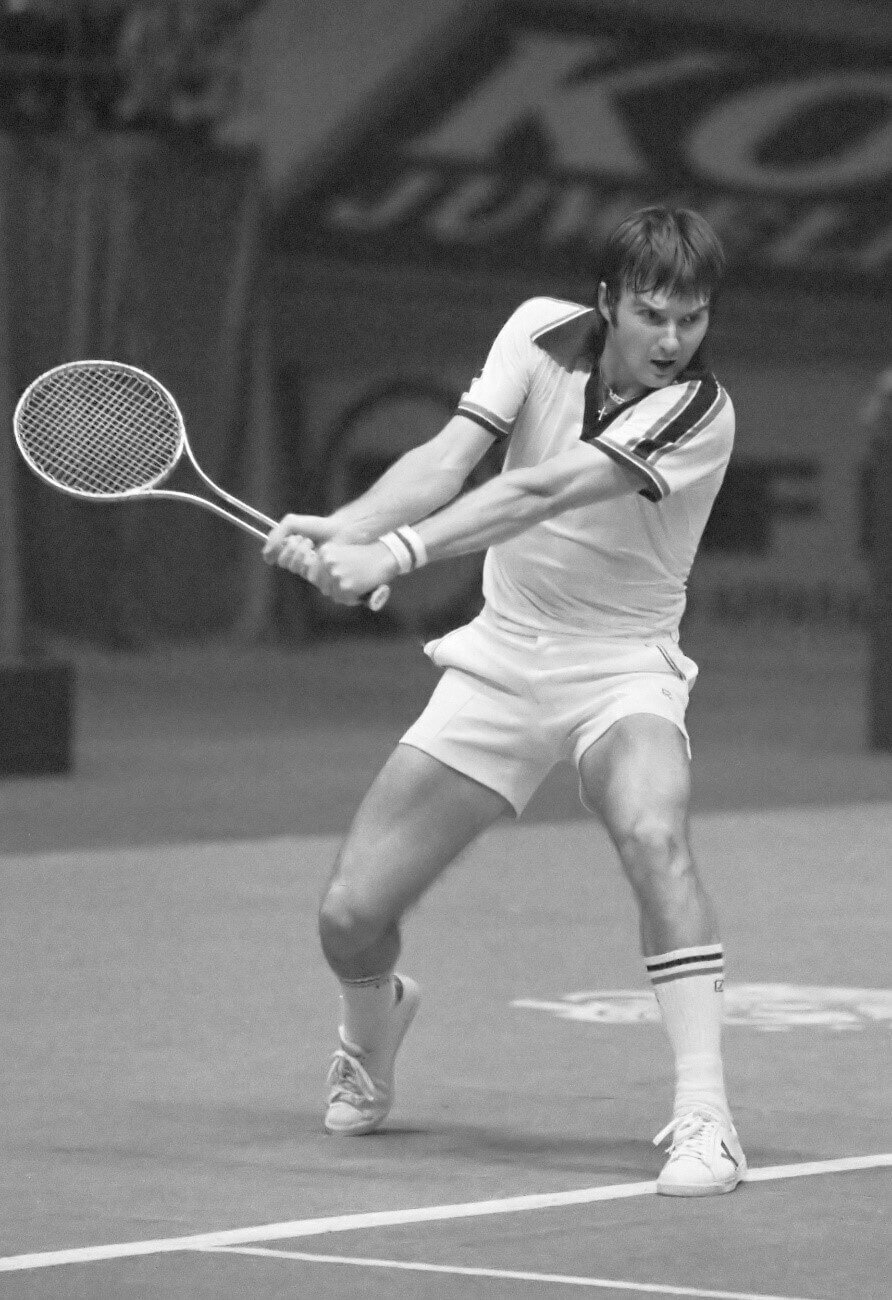

The Wilson T-2000 only truly arrived when Jimmy Connors used it to win three Grand Slam titles in 1974, embedding it in the wish lists of numerous tennis fanatics. The racket became synonymous with Connors’ name who used it to dominate the men’s circuit throughout the latter half of the 70s. So deep was his allegiance towards the T-2000 that he stockpiled every last model he could find when Wilson took it out of production in the 80s.

In the larger scheme of things, the T-2000 was heavy and not powerful enough to affect the serve-and-volley style of play. However, it transformed the very fabric of the sport, setting off an era of consistent technological evolution after almost a century of stasis. The success of the T-2000 compelled fellow tennis professionals to experiment with their choice of racket.

Fellow American Arthur Ashe collaborated with Head to develop the racket manufacturers’ first composite racket. The Arthur Ashe Comp 2 had an aluminum and plastic frame and was customized to suit Ashe’s playing style.

“I was using a new one [wooden racket] every week because they would go soft in the head and break after several days of hard play. I recognized the potential of the racket [aluminum composite] and soon found myself testing dozens of different rackets. We eventually reached our goal of building a racket that would last me a minimum of one month without any deterioration.”

He went on to create history with the Comp 2, becoming the first African-American to win the prestigious Gentlemen’s Singles Championship at Wimbledon in 1975 after getting the better of Connors in the final.

Changing Times

Most top tennis pros, however, stuck to the wooden frames in the 70s. Even Billie Jean King went back to using them. Most of them would transition to the lighter and more powerful graphite frames in the 80s, when it became imperative that sticking with wooden rackets would equate being left behind. John McEnroe started his career with the fabled Dunlop Maxply Fort but became one of the first top tennis players to shift to a graphite frame with the Dunlop Max 200G in the early 80s. Martina Navratilova and Chris Evert would soon follow suit with their shift to graphite with the iconic Yonex R-22 that Navratilova won three Slams with in 1984, and the Wilson Pro Staff respectively.

Some found the transition a little harder. The Ice Man of tennis, Björn Borg dominated tennis with his Donnay wooden frames. Upon his return after an unprecedented 9-year sabbatical, Borg decided to stick to the wooden frames he was accustomed to when he left tennis at his peak in 1982. “I tested other rackets, but I feel at ease with my old one,” he said. “Many claim that it’s impossible to play tennis with a wooden racket nowadays. I know it’s possible.” Needless to say, his return failed miserably as he failed to register even a single win.

The change in the composition of racket frames wasn’t the only path-breaking advancement in racket technology in the 70s. In 1975, racket manufacturer Weed came out with the very first oversized tennis racket. Weed’s oversized aluminum frame failed to gain traction, however, and it wasn’t until the Prince Classic, designed by legendary engineer Howard Head, entered the market in 1976 that oversized rackets became popular. After picking up tennis as a hobby, Head realized that the smaller sweet spot of the 60-70 sq. inch conventional rackets would cause the racket to twist in his hand whenever he hit the ball off center. And thus, to increase the margin of error in tennis strokes, he designed the Prince Classic which had a 110 sq. inch head size and consequently, a much larger sweet spot.

Despite that, most tennis pros were still apprehensive about using oversized rackets. 16-year-old Pam Shriver gave the Prince Classic some much needed credence with her mesmeric run to the U.S. Open women’s singles final in 1978. Shriver stunned world no. 1 Martina Navratilova in the semi-final to become the youngest finalist in the competition’s history. The startlingly tall teenager battled hard with her 110 sq. inch weapon in the final but eventually fell short, losing 7-5 6-4 to three-time defending champion Chris Evert.

Fast forward to 2020 and all tennis professionals or tennis enthusiasts for that matter, use rackets with a much larger head size than what was the norm when Shriver embarked on her historic run.

Another special aspect of the racket Shriver used was the composition of its strings. The Prince Classic deployed the newly developed nylon strings instead of natural gut. These were more durable and did not retain as much moisture as gut strings. This would prove to be a seminal innovation as the subsequent development of polyester strings would make it easier for players to add more spin to their shots, changing the game forever.

The Hard-Court Revolution

The 1978 edition of the U.S. Open is also memorable for being the first Grand Slam event ever held on a hard court. Before 1975, three of the four Majors – Australian Open, Wimbledon and US Open were held on grass while the French Open was held on clay. After a brief switch to green clay between 1975 and 1977, the tournament moved from the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills to the hard courts of the newly constructed USTA National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadows. “Jimmy was born on this stuff – this is his court,” Borg said after losing the men’s singles final to Connors.

Hard courts had been used in official tournaments since the 1940s and thus, playing a Major on the surface wasn’t completely novel for tennis professionals. The surface is almost as fast as grass, but has a higher and more consistent bounce. Grass is more susceptible to wear and tear, and hence, prone to low, uneven bounce. The prevailing tactic on grass surfaces at the time was a low and hard sliced approach shot which made it harder for the opponent to hit a passing shot or a lob. Wooden rackets didn’t help. We are used to watching the likes of Nadal and Federer dip a powerful passing shot beyond the best of exponents of the net game, rendering even the most brilliant of approaches ineffectual. The difficulty of inducing topspin on the ball with the much smaller sweet spot of heavy conventional wooden frames made successful passing shots a novelty. Borg was a stunning anomaly as he soldiered on to title after title on Wimbledon’s grass with his topspin powered baseline game that he somehow mastered with wooden rackets.

The consistent bounce of the hard courts would make it difficult for serve-and-volleyers to hit the conventional sliced approach shot and lead to longer rallies than players were accustomed to on grass. Despite making players more susceptible to injury due to the increased pressure it causes on their joints, hard courts would soon become the playing surface for most top tennis tournaments owing to its all-weather nature and easy maintenance.

Tennis’ structural and technological metamorphosis led to a major boom in its popularity in the 70s and 80s. The Open Era made it possible for the likes of Rod Laver and Ken Rosewall to compete for tennis’ most prestigious prizes again. It also gave rise to the most captivating rivalries tennis between some of the most contrasting personalities that tennis has ever seen.

The Brash Basher of Belleville, Jimmy Connors birthed the gritty, cocksure tennis player in what used to be the gentlemen’s game. Connors and McEnroe’s explosive on-court behaviors were at complete odds with the calm and icy demeanor of their greatest rival – Björn Borg. The only overlapping personality trait between Borg and his American counterparts was that they couldn’t stand losing. Great rivalries were also borne out of distinctive playing styles. It was fascinating to watch Borg and Evert’s steady baseline game pitted against McEnroe and Navratilova’s offensive serve-and-volley approach.

The game moves on

The 70s brought about a major change in playing style with the two-handed backhand. Connors and Evert brought the then unconventional stroke to the big time with their success at the 1974 Wimbledon Championships. Borg would go on to win five consecutive Wimbledon titles with a slightly more unorthodox variant of the modern two-handed backhand. The stroke is easier to as it requires less strength and coordination than the standard single-handed shot. However, it was met with raised eyebrows even after the multiple championship successes of the likes of Borg, Evert and Connors. After Borg’s maiden Grand Slam success at 1974’s French Open, reporters asked him when he was going to shift to the one-handed backhand. Little did they know that the two-handed backhand would go on to revolutionize the sport with the majority of players on tour using it in present day, rendering the single-handed backhand an elusive, dying art.

In the 70s, major tennis tournaments started being broadcasted on television for the first time. The fact that there were only a few available channels on TV in those days led to a surge in tennis’ popularity among the general public at a time when its admiration was limited within the confines of country clubs.

However, the boom wouldn’t have been possible without the technological advancements engendered in the 70s. The increase in the number of public hard courts brought tennis to the masses, while the proliferation of composite overhead rackets made it easier for the general public to learn how to play tennis. Playing with wooden rackets required the precision of a surgeon. The lighter, larger and more powerful rackets were instrumental in simplifying the sport for professionals and aficionados alike. These sweeping changes laid the groundwork for a lot of what we see in today’s game, marking the transition to a more physique-powered, baseline-intensive sport with only the fleeting glimpses of what it used to be before technology took over.

Read More

THE ERA OF THE SHORT GAME- WOODEN GLORY

ANANYA CHANDRA \

THE MAKER AND ITS GAME

THE DAY SÖDERLING TOPPLED THE KING OF CLAY

ATUL KUMAR MAURYA \

THROWBACKS

WIMBLEDON 2009 MEN’S SINGLES FINAL: ONE FOR THE AGES

ATUL KUMAR MAURYA \

THROWBACKS